The Giant’s Ring

Giant’s Ring Introduction

The Giant’s Ring is Northern Ireland’s very own ancient Neolithic gravesite. It dates back to around 2700BC and in the centre is the bare frame of what once was a chambered grave, an cairn from times of old. Throughout Britain we acknowledge our ancestral roots, and we recognise these ancient pagan sites as historic and protect them. However also throughout Britain is the dark site of the majority of these mass graveyards that we overlook. Ancient pagan burial grounds are often the most haunted sites and have the strangest stories revolved around them. In time we may come to understand the magic of these places better. There are more recent and sinister events also recorded upon this mound. That of Necrophilia, demonic worship and child sacrifices.

The Giant’s Ring,Ghost Hunting At The Giant’s Ring

Ghost Hunting Within the Giants Ring

The Giants Ring have caused a number of stories of unusual activity, some of them more magical than paranormal. It has terrified visitors for hundreds of years but that comes as no surprise.

The Hill Itself

All of the usual activity has been witnessed here over the years. Orbs of light, whispered voices, shadow figures etc… All regularly seen. However there is another form of paranormal activity here, something that could even be unique. When people have been walking across the mound a strange white mist comes from the ground itself and engulfs all who are on top. It is so thick that you can’t see 10m in front of you. Obviously this has terrified many people. It is well known that families have been separated in the mist. Is this the aim of whatever is causing this phenomenon? The mist appears even on the hottest of summer days.

One person’s account of this precise phenomena is that of a young family. It was a sunny winter day when we they there, the mother and Aunt stayed near the car as the children ran around. They then walked up to the top of the circular hill and could see the menhir in the middle, and the other side of the ring beyond it, so they walked into the middle. As we were looking at the menhir, it became very cold and foggy, and soon they couldn’t see the hill that surrounded them. The younger sister started getting upset, so they decided to walk back to the car, both of the siblings walked into the mist in the right direction, but ended up coming back to the menhir. They tried another 2 times to leave, but kept getting lost in this thick mist, and coming back to the menhir. Soon they were all getting a bit teary, so the younger brother (who would later join the Army) came up with an idea. He’d run out into the mist, and keep their voices behind him. Eventually when he got to the hill, he’d call, and the younger sister would run to him, with the older brother’s voice behind her. He runs into the mist, by this point all crying and screaming, but soon enough, he calls that he’s found the hill. The younger sister then runs off towards him, and the oldest is left alone next to this menhir, he reported that never been so afraid in all my life. When they called, he ran like the very hounds of hell were behind him. he found them, and sobbing, they ran to the top of the hill to leave the ring, and as they got to the top, the mist lifted, and again you could see across it, the menhir in the middle, and the far side of the ring beyond. No mist whatsoever. They ran to mum, who was confused at first, because according to her, it had never changed from sunny, she’d seen no change in the weather.

This is not the only account of this happening people getting lost within the mist and always ending up back at the druids centre piece. Or indeed people outside of the ring seeing any mist at all. So it would seem that the minds of the people inside get affected. This is one of the favourite tricks of dark entities to play with the minds of the living to create fear and isolation.

The Menhir

The Menhir is the small druidic alter placed directly in the centre of The Giants Ring. Thought to once be a burial chamber there has been strange sightings around it for centuries. People have reported seeing figures all around it but not just one, groups dressed in black or white robes with their arms raised in a tight circle all looking directly the alter with a faint chanting coming from them. People have also gone into a trance like state when looking at the altar. Some even claiming to see visions of women and children being cut open on top of it.

What was the use of this hill? It is an ancient burial ground, but why have satanic cults been attracted to these sites for years. Do they believe that the spirits of old who worshipped the same gods they do will arise? Or do they simply enjoy the blood spill and evil. Whatever is on this hill is intelligent and not friendly.

Ghosts of The Giant’s Ring

Ghosts of Giants Ring

The Robed Figures

Irish folklore and history is full with stories of magic. The Giants Ring has been at the centre of these stories for a long time. There have been figures seen in the centre for many years. Dressed in black or white robes and chanting around the stone, looking like they are performing some kind of ritual. However nobody has ever stayed long enough to see them leave, few say that the figures simply vanish but that could easily be superstition. We cannot be sure if these figures are ghosts or living people, but with a site steeped in dark history there is every possibility that the men and women that created the haunting here still enjoy terrorising the living.

There are similar sites around Ireland and the world. To be a druid is not always sinister however in times of old it was practise to sacrifice humans and animals on stone altars and then set the remains on fire. Those practises are rarer today than ever before, but that does not mean it does not exist. Pagan rituals, witchcraft, demonic worship. They are all known to pretty much one in the same thing, with the same result. These people are worshipping what they call the old gods, gods of element. Today we call them demons, demonic worship in any form has a purpose. They aim to connect with their gods by opening portals. This is some deep spiritual beliefs and something we tend to steer away from. But the things these rituals leave behind something that was love to tackle.

![]()

The Giant’s Ring Location

![]()

A lOOk Around The Giant’s Ring

Additional History On The Giant’s Ring

The prehistoric Giants Ring in the townland of Ballynahatty lies only five miles from Lisburn and four miles from the centre of Belfast Today it dominates the Lagan Valley Regional Park from its isolated sandy plateau caught in a loop of the River Lagan. It is still immensely impressive consisting of a sub-circular enclosure, 200m (220 yds) across defined by a 4m (13 ft) high grass-covered bank with a top flattened by generations of Sunday strollers. It was probably built at the end of the Neolithic or the beginning of the Bronze Age around an earlier Neolithic passage grave. Most of the grave’s massive stones are still in position, though one of the roofing slabs has slipped and the original covering mound has been removed. The only other visible site on the plateau is a large stone set on its side at the western edge of the natural ridge. This has been incorporated into the field bank to the north-west of the Ring. (see fig. l).

It would have taken about 70 000 man hours to construct the Giant’s Ring (Mallory and McNeill, 1991,79) but what could have prompted this great input of labour? The first person to attempt an answer was the antiquarian, Henry Lawlor (Lawlor, 1918) in 1917. With a consortium of local landowners who raised the finance, and presumably with their estate labourers to do the digging, he trenched 500m (550 yds) of the inside of the Ring, dug a section three quarters through the bank and put a circular trench around the passage grave. He finally dug four feet down under the capstone but was only able to find a porter and a lemonade bottle (from a previously unrecorded “excavation”) and fragments of burnt bone, probably from the original cremation. All this was achieved in one week. Though extensive, Lawlor’s hurried excavation revealed little about the function of the Ring and, even for the time, his standard of recording was very poor. His excavations showed that the depth of topsoil increased from 0.45m (1.5 ft) near the centre to I.8m (6 ft) at the inner edge of the bank. (Lawlor, 1918 16). He failed to see that the bank material had been dug out of a broad, shallow internal trough which gives the enclosure its present appearance of an upturned saucer. He preferred to think that this shape was natural and that the stones comprising the bank were ‘…carried by the hands of a large number of workers from the country round.: (Lawlor, 1917-18,21).

|

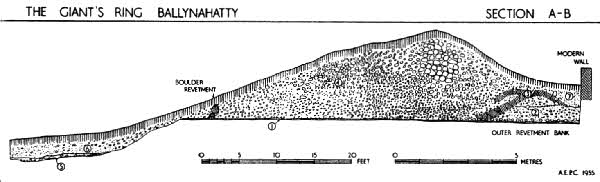

| Fig.2: Drawing of an excavated section cut through the rampart of the Giant’s Ring on the north side by AEP Collins in 1954. Interior quarry ditch on left and 19th century ‘modern’ wall at right. Reproduced by permission of the Ulster Journal of Archaeology. |

It was to be nearly forty years before a modem scientific excavation was undertaken at the Ring. In 1954 AEP Collins of the Archaeological Survey demonstrated conclusively the existence of the inner quarry ditch (Collins, 1955 44-50) and found that not only was there originally a small outer marker or retaining bank, but that the inner face may have been consolidated by a facade of stones (see fig.2).

We can speculate that whatever activity went on inside the enclosure, it had to be contained by the massive bank. If the Ring was a defensive structure we would expect the wall to be on the outside and a ditch beyond whereas the reverse is the case. It is possible that the bank was actually constructed with a flat top (instead of having been eroded to the present shape) in which case it may have provided a platform for spectators to observe ceremonies. The size of the interior space may relate directly to the number of people to be contained therein or simply to the nature of the activity taking place. Of course the larger the enclosure, the greater the bank circumference and the more room in the ‘stands. Therefore, the activities may have been contained and separated from the outside world with perhaps only a section of the population being able to participate within the enclosure. Alternatively, they may have been witnessed by a much larger section of the population on the grandstand provided. A flattened top may imply the latter. Either way, the focus of activity must surely have been the passage grave around which the Ring is laid out (Hartwell, 1991,14).

|

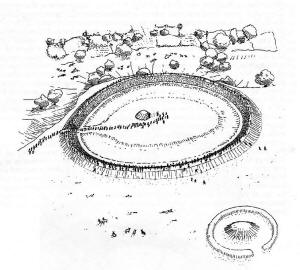

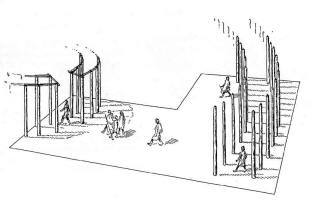

| Fig 3: Conjectural reconstruction of the Giant’s Ring as seen from the North. |

This arrangement of an internal, flat-bottomed; trough’ providing the quarry material for an outer bank is similar to a number of other enclosures in Ireland, such as Dowth Hall, in the Boyne Valley, Co. Meath (Hicks, 1975,70) and ‘Rath Maeve 1 km south of the Hill of Tara (Stout, 1991,257). These enclosures can be described as ‘hengiform and are similar to the henges of southern Britain where the trough is replaced by a more substantial ditch and there are one, two or four entrances. They vary enormously in size but the general absence of primary domestic remains points to the original function being ceremonial. Perhaps they were the churches of their day with the Giant’s Ring representing a regional, higher status site similar to a cathedral.

The conjectural reconstruction of the Giant’s Ring brings together a number of the ideas outlined above (fig.3). Here the Ring stands on the southern edge of the plateau overlooking the fertile land of the Lagan Valley. The internal slope of the bank is lined with stones and the bank has a flat top on which people crowd to view the spectacle unfolding within. The passage grave, embedded in an earthen mound provides the focus of activity. The quarry ditch can be seen between the two. In the right foreground is a circular bank (BNH3) first seen as a crop mark in an aerial photograph (see fig. l). This was excavated in 1991, when the remains of a stoney bank were found on the eastern side. The central area had been removed by quarrying to a depth of 3m (10 fl) and backfilled within the last two hundred years. It is tempting to relate this site to an eighteenth century reference:

| Contiguous to this Rath (i.e. the Giant’s Ring), there was a small Mount that same of the Neighbours dug through, in order to get Stones for Building; and in the middle thereof a great Quantity of Bones was found (Harris, 1744,218). |

Did the ‘Neighbours remove the mound then, finding that the site stands on a bed of fine quality sand, decide to quarry out the subsoil? A central burial mound has been reconstructed. This may have been a smaller version of the Giant’s Ring with its central passage grave or the remains of a large Bronze Age round barrow. In 1989, air photography revealed a line of three small round barrows only 75m (82 yds) to the south west.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the area to the immediate north and west of the Ring was being cleared for agricultural use, large quantities of human bones were being turned up by the plough. One of the tenant farmers, MR. David Bodel, who farmed the land to the north-west of the Ring, found a circular stone chamber and some skulls while he was digging potatoes. This was reported in the Belfast Newsletter on November 21, 1855:

| ‘…they came across a broad, flat stone, which, upon being removed, proved to be the entrance to a tomb…Two boys who were in the field at the time, immediately descended into the place and examined it. !t is about six feet in diameter, and four in depth, and is nearly round at the base…Five slabs are placed as supports at equal distances round it, and in one of the compartments formed by them, was discovered an urn filled with bones, and three skulls, two of which are perfect; the third was, by accident, broken. From the appearance of the bones, it is evident that they had been burned previous to being deposited in the urn; but the skulls had been placed in the sand in their natural condition…’ |

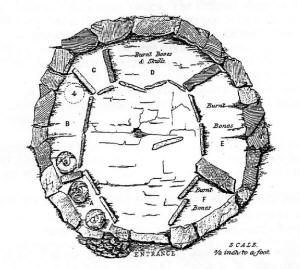

By the end of that week, Robert McAdam, owner of the Soho Foundry, Gaelic scholar and editor of the Ulster Journal of Archaeology had visited the site with his friend, MR. Getty, and other members of the Belfast Natural History and philosophical Society. Their exceptionally well documented report appeared in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology (McAdam and Getty, 1855,358). Both accounts describe a radially segmented, stone lined chamber, with a corbelled roof, sunk into the ground (see fig.4). McAdam says that the top of the structure was 45 cm (18 inches) below ground level and may have been covered with small stones to form a cairn. Although the small boys entered through the roof of the chamber, the original entrance was clearly seen on the east end of the structure, blocked by a removable stone, at the floor depth of 1.4m (4.5 fl). Unless there was a ramp running down to it, access to the entrance was clearly going to be a problem. Four pottery urns contained burnt bone and elsewhere packages of burnt bone were separated by long thin stones clearly indicating at least five, probably many more, cremated individuals. The unburnt bone indicates at least five more, but there are no complete skeletons. This suggests that although some of the bodies were cremated, others were defleshed outside the tomb, simply by being buried for a period of time and then dug up again or, more likely, being exposed to the elements in a mortuary enclosure -a process called excarnation. This would prevent the larger bones from being removed though the smaller ones could be taken by scavenging birds and rodents which would pick at the bones. Only some of the bones of the individual would therefore be placed in the tomb. Some cow and sheep bones suggest that joints of meat may have been placed in the tomb as well, presumably as food offerings for the dead in the afterlife. The mixture of burial customs (cremation in pots, cremation in packages, excarnation) all strongly suggest that the tomb was used over a long period of time. At least one of the pots was of Carrowkeel Ware, a type of pottery associated with passage graves and the late Neolithic, though there may be evidence for the use of the tomb into the succeeding early Bronze Age. If this is the case then the location of the subterranean entrance must have been clearly defined on the surface, possibly by a ramp.

|

| Fig.4: Plan of the 1855 tomb as drawn by McAdam |

In 1856, some of the pottery was presented to the Royal Irish Academy by Lord Dungannon (the enlightened landlord from Belvoir House and the man who built the protective wall around the Giant’s Ring). The bone material and the rest of the pottery went into the collection of the Belfast Natural History and philosophical Society which forms the basis of the present Ulster Museum collection. Two of the skulls were sent to the Anatomy Department at Queens College (now the Queens University of Belfast) and one remains in their museum. More prehistoric material survives from this one site than has been found in all the other excavations in Ballynahatty until the start of the 1992 season. McAdam and Getty also reported David Bodel’s reminiscences of the various archaeological features which he or his forebears had removed over the previous fifty years. They included a standing stone, two flat cemeteries, a cemetery mound containing several stone cists, several scattered cist burials, a ritual pit containing burnt material, a mound containing a megalithic grave and various carved stone artifacts. Similar sites were being found in the adjoining fields of his neighbours, MR. Thompson, MR. McKeown and MR. Russell – effectively the whole area of the plateau. The sacred ground around the Giant’s Ring therefore acted as a magnet for possibly hundreds of burials through the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages, most were probably in simple unmarked graves. We can therefore stretch our analogy with the churches a little further by including the associated graveyard. Though we know that these sites existed, we do not know the full extent of the cemeteries or the actual location and date of the burials. To attempt to find this out we must now move forward to the twentieth century and examine a technique which has revolutionised the location of sites.

In a period of exceptionally dry weather, certain crops (especially cereals) standing over damper, buried pits and ditches stay greener for longer as the surrounding crop ripens to a lighter colour. This happened in 1989 when the rings of the Bronze Age barrows could be seen, but even more exciting was the appearance of a large oval double-palisaded enclosure 70m x 90m in extent and with a similar but smaller enclosure at its eastern end.

Assisted by generous grants from the Conservation Service – Historic Monuments Branch and from the School of Geosciences at Queen’s University, this site (Ballynahatty 5) has been excavated for three seasons and a further season was undertaken in 1994. Over 500m square of excavations have uncovered a more complex set of remains than the air photographs suggest.

|  |

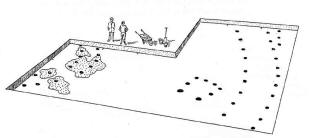

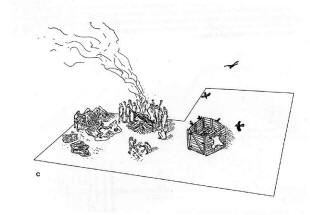

| Fig 6a: Simplified view of the excavated surface of Ballynahatty 5 at the end of the 1992 season | Fig 6b: The ‘temple’ phase showing the main enclosure and the inner, smaller enclosure. |

The outer enclosure consists of post holes, 2m (6.5 ft) deep and radially paired that may have held free-standing posts the height of telegraph poles. The earth-fast lower section had rotted in situ but scatters of charcoal suggest that the superstructure had probably bumf down. The charcoal found in the post pits of the large outer enclosure have been dated in the Radiocarbon laboratory at Queens University to between 3018 and 2788 BC. This is over two hundred years earlier than the great pyramids in Egypt, contemporary with the earlier phases of Stonehenge and two hundred years later than the Newgrange passage tomb. At least 250 mature trees, probably oak, were felled and hauled to the site and each post pit would have taken over 24 hours of digging with antler picks to reach the required depth. The whole enterprise could have taken over 15,000 work hours to complete. If the posts were carved in any way it would have taken considerably longer. There appears to be no formal evidence although not all of the enclosure can be seen in the air photograph.

At present, the greatest hindrance to interpretation is the lack of radiocarbon dates over the rest of the site. It is therefore not possible to say which, if any, of the other features seen in Fig.6a are contemporary with the main enclosure. But, based on the limited information available, the reconstruction of Ballynahatty 5 has been shown in two phases.

In the initial phase of monument building the inner enclosure, like the much bigger outer one, consisted of two concentric lines of post pits about 2m deep. However, the character of these is different. They are not radially paired but have the same regular interval along both the inner and outer ring. Thus there was an inner ring of about 19 posts and an outer ring of about 30 posts. Each pit had an associated ramp down which to slide the post and in some of the sandier pits gouge marks could be seen where the heavy post had rammed into the opposite side of the pit. There is a clear entrance towards the south west. When an excavated timber circle was reconstructed in Wales recently (Gibson, 1992,84) there did not appear to be enough visual distinction between the rows of timber posts as seen from the outside, so lintels were added (as can be seen at Stonehenge). The Ballynahatty enclosure was probably not roofed but may also have had lintels. This structure clearly provided an inner focus to the activities and may be regarded as a temple. Completion of the excavation will be necessary to throw more light on this important problem. As with the Giant’s Ring and its passage grave, the focus here involves death and burial. The only human burial found during excavation was a cremation, between the two rings of the inner enclosure, laid in a small pit lined with split stones.

The second phase takes place after the temple superstructures have been razed or removed but before the memory of this area as a focus of ritual has been lost.

|

| Fig 6c: The ‘mortuary house’ phase |

Immediately within the line of outer enclosures was found a small rectangular setting of eight portholes open towards the SSW. These portholes were 0.8m (3 ft) deep supporting posts about 2.5m (8 ft) high. There may have been a gate enclosing the fourth side. This may have been a small mortuary house just large enough to hold an extended body during the process of excarnation. Shallow pits full of black, charcoal rich soil and containing end scrapers and fragments of burnt animal (especially pig) bone suggest that feasting or animal offerings were also taking place after the inner enclosure had been dismantled. Quantities of waste flint flakes showed these food or hide processing scrapers were being manufactured on site. All the burnt remnants of the feast including the ‘cutlery’ were carefully buried, perhaps as an offering to an earth god, while the corpse lay m the mortuary chamber exposed to the skies. The final act of he burial rite would be the eventual collection of the cleaned and bleached bones and their deposition in a stone chamber – a house of eternity and a suitable resting place for the ancestors.

Ballynahatty should therefore be seen as a focus of community ceremony and death rituals in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Lagan Valley. A place close to but set apart from, the rich lowlands which probably supported a substantial prehistoric population. It was obviously a society which was capable of being well organised. There had to be some sort of social cohesion, with some imposed or inherited authority, that was able to motivate or coerce the population to produce constructions of the size of Ballynahatty 5 or the Giant’s Ring. The apparent ritual function which underpins these monuments does strongly suggest some form of spiritual leadership. However, we must not forget that the implication of excarnation is the preservation of bones and their deposition in what may be regarded as family tombs. It is a desire to maintain tangible links with the people of the past who had lived and toiled on the same land. This is especially important in a society where life expectancy may have been as little as 30 years. In effect they were reinforcing ancestral rights to a particular territory and to the Neolithic farmers, land must have been their most important possession.

The excavations at Ballynahatty would not have been possible without the kind permission of the owner, Mr James Thompson. I must also thank my assistant Ms Lucia McConway and the students of the Department of Archaeology at Queen’s University, Belfast, members of the Ulster Archaeological Society and many volunteers who have given willingly of their services.